GERMANENGINEER.COM isn’t just about advice or reviews. It’s taking an active role in helping automakers and equipment manufacturers build and assemble the actual equipment used in the production of electric vehicles.

Kanban has proven to be the best way to create positive change and rapid progress in EV manufacturing projects. The Kanban approach is especially useful for managers who need to adapt existing project teams to new realities. Author of the bestselling book “Kanban“, David J. Anderson writes: “Over the past decade, I’ve been challenged to answer the following question: As a manager, what actions should you take when you inherit an existing team, especially one that is not working in an agile fashion, has a broad spread of ability, and is, perhaps, completely dysfunctional? (…) As a manager in larger organizations, I’ve never been able to hire my own team. I’ve always been asked to adopt an existing team and, with minimal personnel changes, create a revolution in the organization’s performance. I think this situation is much more common than one in which you get to hire a whole new team.”

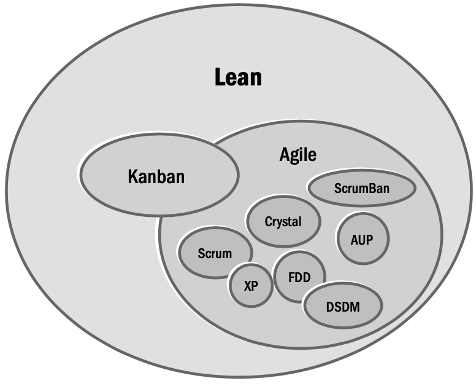

Kanban, like Agile, is an important subset of Lean Project Management. Kanban was introduced by Taiichi Ohno to manage the flow of materials and information within the Toyota Production System. The inspiration for Kanban came from observing how customers interacted with products in U.S. supermarkets. In the supermarkets, all products sold were recorded at the cash register, and then lists of products purchased were sent to the supply department for ordering from manufacturers. In this way, store shelves were always stocked with the right number of products, with no shortages or surpluses. Taiichi Ohno took the supermarket principle and applied it to Toyota’s factories. Parts for assembly began to be delivered to the plants in small batches when needed, freeing up warehouses. This involved not only working with suppliers, but also internal operations between Toyota’s own facilities.

The goal of Kanban is to minimize the amount of work – we produce “only what is needed, when it is needed, and in the amount needed”, thus freeing up time for (self-) improvement. In the free time, a team or a person is given the opportunity to reflect on their work and how it can be improved. Here is an example: Typically, 80% of a person’s work is largely repetitive. On a regular basis, the expected completion time is shortened, requiring some critical thinking to meet the new, tighter deadline. The person must ask himself: “What am I doing? Is there a better way to break the work into standardized procedures? How can I make the standardized procedures more efficient? Are all these procedures necessary to get the work done?” This approach echoes Albert Einstein’s wisdom about spending more time thinking about a problem than rushing to find a solution: “If I had an hour to solve a problem, I would spend 55 minutes thinking about the problem and 5 minutes thinking about solutions.”1 By thinking slowly and acting quickly, a person learns to find efficient and resourceful ways of working.

A Kanban system is a visual workflow management tool that helps individuals and teams visualize their work, limit work in progress, and maximize efficiency. Originating from lean manufacturing practices at Toyota, Kanban uses cards (often on a digital board) to represent work items. Each column on a kanban board represents a different stage of the workflow, and the movement of cards from one column to the next indicates the progress of the work. A digital board provides accurate information on how long a card has been in each column and how quickly all cards related to a task have moved from the leftmost to the rightmost column. By analyzing this data with statistical tools, it is possible to observe how the completion time is decreasing, i.e. how the process of (self-) improvement of an individual or a team is progressing.

Kanban creates a revolution in personal and organizational performance, freeing up both human and machine time for improvement and the creation of new technologies. Self-improving people, equipped with better skills and a deeper understanding of their work, contribute significantly to the continuous improvement of manufacturing processes. They are also the foundation of strong agile project teams. Such teams can be set extremely high goals to find radically new ways of doing things. They can create new assembly line technologies, modern workplaces, and high-quality jobs.

Toyota developed six rules for the effective application of Kanban.2 Based on these rules, David J. Anderson has developed a methodology for implementing Kanban, which he calls “Recipe for Success” – six rules for a leader to adapt an existing team to new realities. By following these rules, rapid improvement can be achieved with little or no resistance from the team. They help the team improve both standard operating procedures (SOPs) and the ability to identify immediate or potential risks.

The following is a description of the six Kanban rules and how GERMANENGINEER.COM applies them to help automakers and equipment manufacturers build and assemble the manufacturing equipment used in the production of electric vehicles.

1. Never Pass on Defective Products

David J. Anderson defines this rule as “Focus on Quality” and writes: “The Agile Manifesto doesn’t say anything about quality. (…) So if quality doesn’t appear in the Manifesto, why is it the first [rule] in my recipe for success?

Simply put, excessive defects are the greatest waste…” Defects are a kind of waste, because they put effort into production that brings no benefit. The later you find a defect, the more expensive it is. Therefore, the goal is to catch defects early. Defects in manufacturing equipment can significantly impact project schedules, causing delays due to necessary rework or repairs.

Implementing rigorous quality control measures at every stage of the manufacturing process ensures that defects are identified and addressed promptly. This can include regular inspections, automated testing, and statistical process control methods such as Six Sigma. Preventive measures, such as Failure Modes and Effects Analysis (FMEA), help identify potential failure points and implement solutions before they become significant problems, thereby reducing the incidence of defects. Investing in employee training and development ensures that employees have the skills and knowledge to identify and address potential quality issues, resulting in fewer defects.

At GERMANENGINEER.COM, we prioritize the first rule of Kanban to help automakers and equipment manufacturers build and assemble the manufacturing equipment used in EV production. By implementing rigorous quality control measures during design, assembly and commissioning, we ensure that automakers receive reliable and efficient manufacturing equipment.

For a detailed discussion on how GERMANENGINEER.COM applies the first rule of Kanban to enhance quality in manufacturing equipment for electric vehicles, see the post Focus on Quality.

2. Take Only What Is Needed

Toyota articulates this principle as: “At each stage, use only the amount of labor or materials needed for the next stage of production.” The saying “Don’t Bite Off More Than You Can Chew” effectively conveys the idea of not overestimating one’s capabilities.

This principle is designed to boost efficiency by reducing the amount of unfinished work, which in turn reduces the completion time. Little’s Law describes a linear relationship between the amount of work in progress and the average completion time. This logic supports the use of a Kanban system to limit the amount of work in progress.

In the context of limiting work in progress, the kanban system is particularly beneficial. By limiting the number of work items that can be in progress at any given time, Kanban helps prevent overloading and ensures that resources are focused on completing tasks rather than starting new ones. This aligns perfectly with the principle of using only as much labor or material as is needed.

The visual nature of the kanban system makes it easy to see which team members are overloaded. Teams can quickly identify and make necessary adjustments, promoting continuous improvement. This not only increases efficiency, but also ensures a more predictable and reliable delivery process, ultimately contributing to better project performance.

3. Produce the Exact Quantity Required

Toyota formulates this principle as: “Each stage of the production process should produce only the amount needed for the next stage.”

The idea is to reproduce and replenish only what has been consumed. If the next process requires four parts, the upstream process produces four more of those parts – no more and no less. This maintains an upper (not lower, as many people think) inventory limit, which is a key feature for achieving the benefits of a kanban system.

The upstream process (e.g. the supplier) also needs to know in time how many parts are left in the supermarket to reproduce more goods more efficiently. In a kanban system, the “supermarket” is an inventory location where items are stored for the downstream process (e.g. customer). For this purpose, the supermarket is the responsibility of the supplier. He is responsible for monitoring the inventory levels in the supermarket and replenishing them continuously. If the customer were responsible for the supermarket, there would be a risk that the restocking order would arrive too late. This could result in delays and shortages.

4. Level the Production

This step is an important and often underestimated part of Kanban.

Large fluctuations in supply and demand mean either a periodic shortage of material in the supermarket, or a much higher level of inventory to cover these large fluctuations. Both options are inappropriate. The first leads to material shortages and stoppages in the downstream process. The second increases the negative impact of inventory.

Reducing fluctuations and establishing a stable workflow, can make production cheaper and more efficient. Production leveling, or “Heijunka,” stabilizes the flow of materials and reduces fluctuations in the production process. Production leveling can take several forms, including:

- Demand Leveling: Deliberate influencing of demand itself or the demand processes to deliver a more predictable pattern of customer demand.3 For example, promoting products during periods of low demand or using promotions to increase demand during slumps.

- Leveling by Volume: Level production by the average volume of orders received. For example, if the average demand is 25 orders per week, but the number varies by day (e.g., Mon 3; Tue 10; Wed 5; Thu 5; Fri 2), it would be wise to implement Heijunka to level production by volume. In this way, a stable workflow can be established, and 5 orders per day can be processed to meet the average demand at the end of the week.4

- Leveling by Type: Heijunka can also be used to manage a portfolio of products. It allows you to level production based on the average demand for each product in the portfolio. The principle remains the same: produce enough of each good to satisfy the average customer demand for the product portfolio. Leveling by type also involves line sequencing: Arranging the order of items on the production line to balance workloads and reduce complexity. For example, if the factory’s ordering system sends batches of high-spec car models down the line at the same time, workers would be required to perform many complex assembly tasks that are not required on less well-equipped cars. By sequencing the line to alternate between high- and low-spec models, the workload is balanced, making the production process smoother and more efficient.

David J. Anderson writes, “…once you balance demand against throughput and limit the work-in-progress within your value stream, magic will happen. Only the bottleneck resources will remain fully loaded. Very quickly, other workers in the value stream will find they have slack capacity. Meanwhile, those working in the bottleneck will be busy, but not swamped. For the first time, perhaps in years, the team will no longer be overloaded, and many people will experience something very rare in their careers, the feeling of having time on their hands.

Much of the stress will be lifted off the organization and people will be able to focus on doing their jobs with precision and quality. They’ll be able to take pride in their work and will enjoy the experience all the more. Those with time on their hands will start to put that time toward improving their own circumstances; they may tidy up their workspace or take some training. They will likely start to apply themselves to bettering their skills, their tools, and how they interact with others up- and downstream. As time passes and one small improvement leads to another, the team will be seen as continuously improving. The culture will have changed. The slack capacity created by the act of limiting work-in-progress and pulling new work only as capacity is available will enable improvement no one thought was possible.”

5. Fine-tune Production

David J. Anderson calls this rule “prioritize” and explains, “If the first three steps in the recipe have been implemented, things will be running smoothly. At this point, management’s attention can turn to optimizing the value delivered,” rather than just the quantity of parts delivered.

“Prioritization should not be controlled by the engineering organization and hence is not under the control of engineering management. Improving prioritization requires the product owner, business sponsor, or marketing department to change their behavior. At best, engineering management can seek only to influence how prioritization is done.”

6. Stabilize and Rationalize the Process

Variability leads to unpredictability, which causes delays and inefficiencies, and can have a significant impact on process throughput and cost.

One of the primary sources of variability is the inherent differences in the tasks or requirements themselves. Some tasks may be large and complex, while others may be small and straightforward. This variability makes it difficult to maintain a consistent workflow. Reducing this variability requires knowledge workers to change the way they work-learning new techniques and changing their personal behavior. For example, breaking large tasks into smaller, simpler procedures can help standardize the amount of work required for each task, leading to more predictable results.

In addition, variability is often unintentionally introduced by poor policy decisions within the organization. Policies that do not consider the nature of the work or workflow can create unnecessary variability. For example, policies that allow arbitrary changes in priorities or scope can lead to constant disruption and rework. By revising these policies to be more consistent and aligned with the actual workflow, organizations can significantly reduce variability. For example, a new prioritization policy might only allow changes to production priorities at specific intervals, such as weekly planning meetings.

Reducing variability has several notable benefits:

- Reducing variability enables resource balancing: Inconsistent task sizes can lead to periods of high stress followed by idle time for workers. By standardizing tasks, the manufacturer can more evenly distribute the workload among workers. This could mean moving a worker from a less busy station to assist in a busier area (and potentially reducing headcount).

- Reducing variability reduces the need for resources: A more predictable assembly line allows the EV manufacturer to streamline inventory management. For example, by stabilizing battery pack assembly times, the manufacturer can reduce the amount of battery packs in the supermarket, thereby reducing storage costs and capital tied up in inventory.

- Reducing variability allows for fewer kanban tokens, less WIP, and results in reduced average lead time: With lower variability, the manufacturer reduces the number of vehicles on the assembly line simultaneously. If they previously allowed ten vehicles in process but reduce it to eight due to more predictable task completion times, they see a reduction in average lead time.

- The Third Critical Step In Problem Solving That Einstein Missed retrieved 6/18/2024. ↩︎

- Kanban – Toyota Production System guide retrieved 6/18/2024. ↩︎

- Production leveling retrieved 6/18/2024. ↩︎

- What Is Heijunka? retrieved 6/18/2024. ↩︎

Leave a Reply